KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI – The brief historical account explores the efforts to establish the first African American banks in the United States.

“For the first African American banks, it was not only about serving as a source of credit for businesses and consumers, but also about providing training opportunities and jobs for African Americans, supporting economic development and, importantly, pride,” said Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City President and CEO Esther George. “This book offers historical perspective on the role of – and the implications of the absence of – minority-owned depository institutions.”

Efforts to establish African American banks began before the Civil War. Let Us Put Our Money Together details the nation’s first black bankers in the 1800s, their challenges, innovation and resilience. Three banks are prominently featured, the True Reformers Bank (Virginia), Capital Savings Bank (Washington, D.C.) and the Alabama Penny Savings Bank (Alabama).

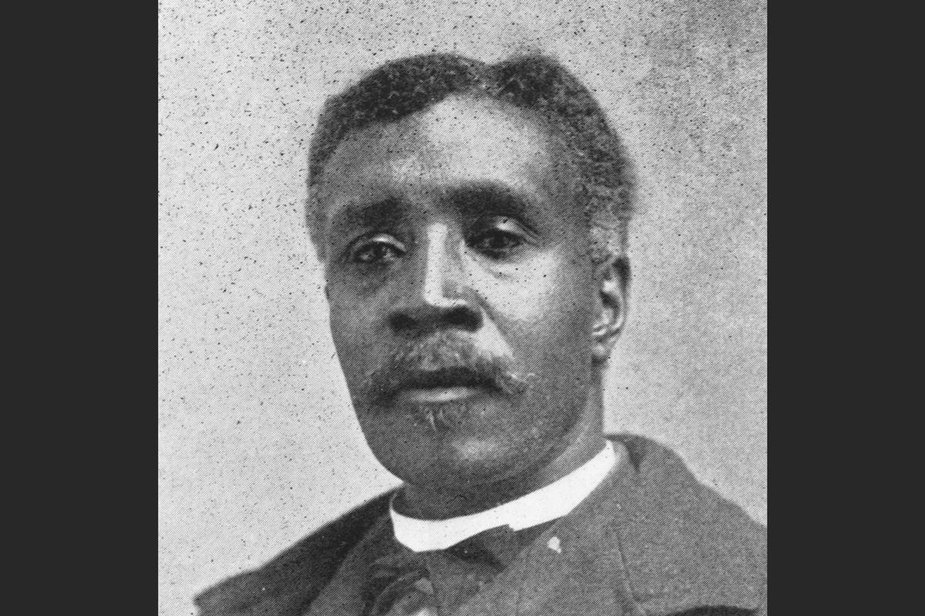

William Washington Browne was a former slave who led the establishment of the United Order of True Reformers, a black fraternal beneficiary organization that assisted its members financially in times of sickness and provided funds for burial costs. After problems were encountered in finding a safe place to deposit funds, the True Reformers established a bank, with Browne serving as president. (Courtesy of the Virginia Museum of History and Culture, VAHM 2003.161.75 (circa 1897))

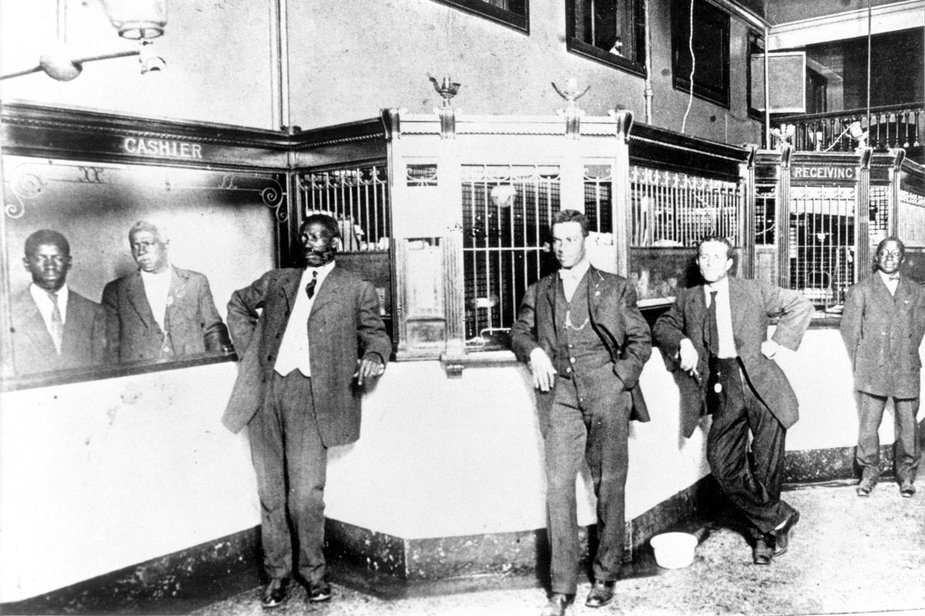

The Savings Bank of the Grand Fountain, United Order of True Reformers operated out of the first floor of a three-story building the Order constructed in 1891. The building, which was also home to the Order’s headquarters, was on the edge of the Jackson Ward area of Richmond, Va. – a neighborhood that soon became known as the birthplace of black capitalism. (Courtesy Virginia Museum of History and Culture, VAHM 2001.660.38 version 1 (early 20th century))

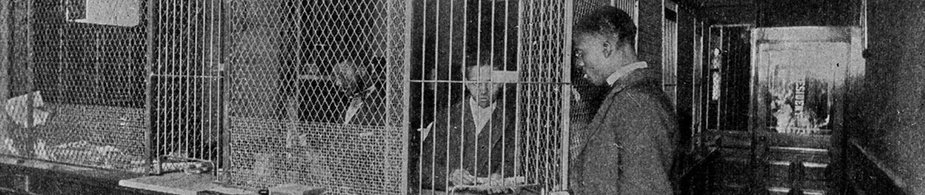

When the Alabama Penny Savings Bank in Birmingham, Ala. opened in 1890 it did not have a state charter, could not pay its staff and accepted deposits on a table. By century’s end, it was a successful state bank, had weathered a major financial panic, was conducting business in a far more appropriate setting and had created an innovative program to increase home ownership among its customers. (Courtesy of the Birmingham Ala. Public Library Archives, image m-6281 (early 20th century))

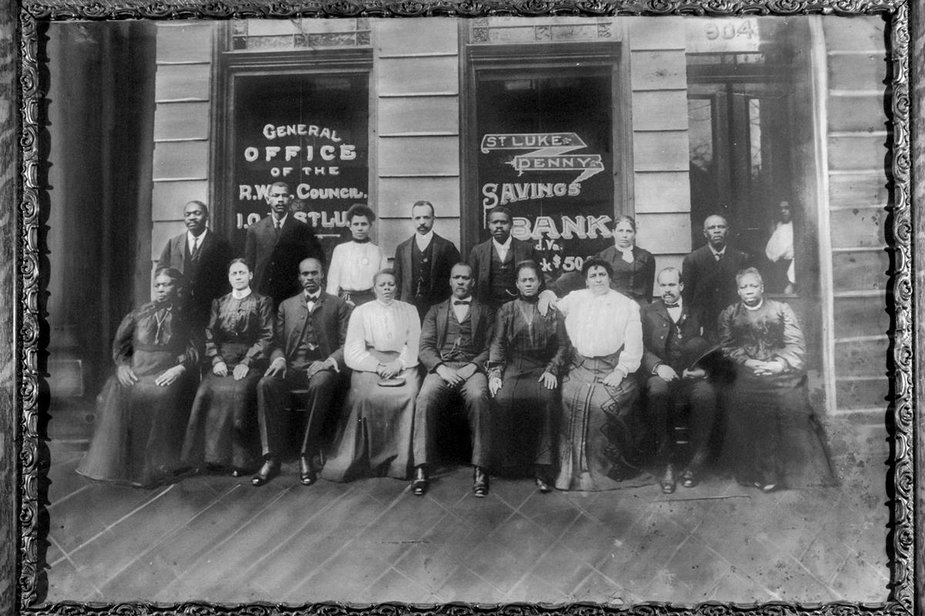

Maggie Lena Walker’s leadership brought success to both the Independent Order of St.Luke and the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank. As the first black female bank president in the United States, Walker became something of a celebrity and is today the most well-known among the nation’s earliest black bankers. (Courtesy of the National Park Service, Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site, MAWA 99-0780 (circa 1905 – 1910))

The leadership of the Independent Order of St. Luke, the parent organization for the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank, outside the St. Luke building in Richmond, Va. The bank was a key entity under the St. Luke banner which also eventually included a retail store, printing press and a weekly newspaper. (Courtesy of the National Park Service, Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site: MAWA 7231 (circa 1903-1905))

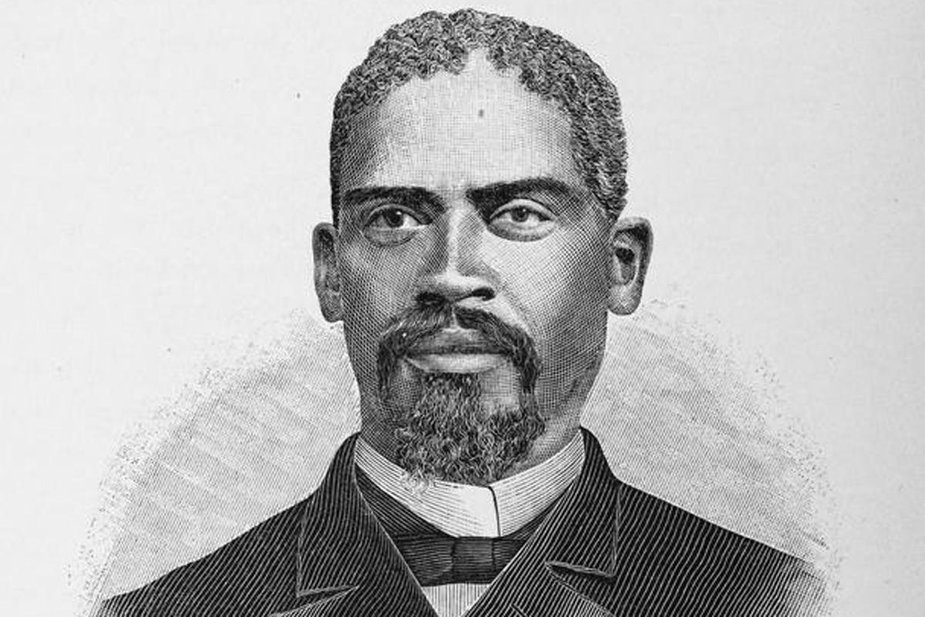

William R. Pettiford reversed the financial fortunes of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala. before turning his focus to banking. Pettiford and the bank’s employees learned about the business of banking, including such aspects as bookkeeping, through somewhat informal training that Pettiford arranged through the city’s white financial institutions. (Courtesy of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library. "W. R. Pettiford" The New York Public Library Digital Collections, (1887), via http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/a5026780-c6d4-012f-1b55-58d385a7bc34 (accessed February 19, 2019))

The book’s title is inspired by Maggie Lena Walker, the first black female bank president in the U.S., who said, “Let us put our moneys together. Let us use our moneys; let us put our moneys out at usury among ourselves and reap the benefit ourselves. Let us have a bank that will take the nickels and turn them into dollars.”

While the book focuses on the history of African American-owned banks, the current number of minority-owned banks in the U.S. have declined. According to FDIC data, over the past 17 years, black-owned banks have declined more than 50 percent, the largest drop among minority depository institutions.

The book is intended to be a resource for educators, historians, financial journalists, banks and more. A complimentary hardcopy can be ordered via the Kansas City Fed website at kansascityfed.org/letusputourmoneytogether. The book summary and a free e-book is also available online.

Let Us Put Our Money Together is the latest installment in the Kansas City Fed’s Centennial Series, short books that explore a number of important themes in Federal Reserve history, banking and economic policy.

As the regional headquarters of the nation’s central bank, the Kansas City Fed and its branch offices in Denver, Oklahoma City and Omaha serve the seven states of the Tenth District: Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Wyoming, northern New Mexico and western Missouri.

# # #

Free copies are now available