The coronavirus pandemic has disrupted tax collections and impelled increased medical spending, with potentially serious financial consequences for state and local governments tasked with a response. These consequences, in turn, could affect the U.S. economy more broadly. The state and local government sector is an important contributor to both economic growth and employment in the United States. In 2019, the sector contributed two-tenths to overall GDP growth. In February 2020, state and local government employment together made up about 13 percent of U.S. total employment. State and local government employment made up an even larger share of employment in the Tenth Federal Reserve District, ranging from 13.1 percent in Missouri to 21 percent in Wyoming._

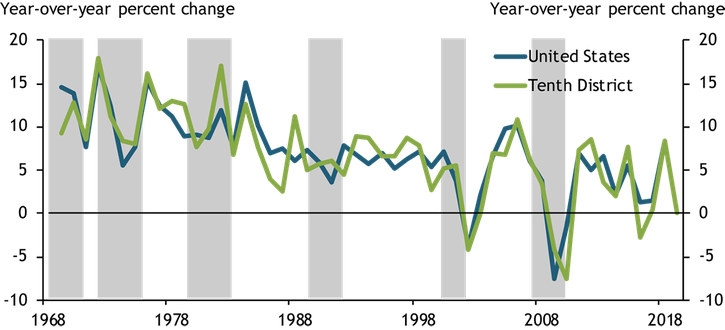

However, the economic effects of COVID-19 on state and local governments may take some time to fully materialize and may persist even as health risks dissipate. During the Great Recession, state and local governments were not a drag on GDP growth until 2010, and then hindered growth through 2013 even as other parts of the economy rebounded. State and local government performance tends to lag business cycles for two main reasons. The first reason is that government spending sometimes increases during times of stress as the demand for safety net programs increases. The second, and likely more important, reason is that state and local tax collections tend to lag business cycles. For example, Chart 1 shows that state tax collections did not reach their troughs until well into the last two recessions.

Chart 1: Real State Tax Collections

Note: Gray bars denote National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER)-defined recessions.

Sources: Bureau of Economic Analysis and NBER (Haver Analytics).

Personal income taxes and property taxes provide two examples of how recessionary effects on tax collections can be delayed. When a state enters a recession and workers’ personal incomes decline, the government will likely feel some effects immediately in the form of lower tax withholding. However, the full effect on personal income taxes will likely not be realized until workers file taxes the following year. Effects on property taxes can take even longer to materialize, as assessments are typically conducted every couple of years.

Although the current crisis is likely to affect state and local finances in similar ways to previous downturns, several unique features have put immediate pressure on state and local governments. First, government spending has risen significantly as states buy medical supplies and set up temporary health facilities to combat the spread of COVID-19. Second, most states have postponed income tax filing deadlines from April 15 to July 15 to align with the new federal deadline, creating a temporary liquidity challenge. Third, shelter-in-place orders in many states are expected to have significantly and immediately reduced consumer spending, thereby lowering sales tax collections. Although food purchases for home consumption have increased, many states exempt groceries from sales taxes.

Currently, two programs are in place to help states weather these near-term challenges. First, in late March, Congress passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, which allocated $150 billion in federal funding for state, local, and tribal governments, including $11.14 billion for states in the Tenth District._ The CARES Act also allocated $30 billion for an Education Stabilization Fund and $45 billion for the Disaster Relief Fund. These funds may help states cover some of the costs associated with COVID-19 and partially fill budget gaps in the short term. Second, in early April, the Federal Reserve established the Municipal Liquidity Facility, which may help to alleviate short-term liquidity issues that arise as a result of delayed tax collections.

These programs may provide relief in the short run, but they are unlikely to fill budget gaps in the next couple of fiscal years as the decline in state and local tax collections intensifies. Many state legislatures are currently adjourned or postponed, but most states must approve next year’s budget by July 1. Although formal revenue forecasts are not yet available, revenue shortfalls are likely to be significant. For example, in Colorado, the cities of Denver and Boulder expect revenues to fall by $180 million and $28 million, respectively (9News 2020; Swanson 2020). Looking ahead, Colorado is bracing for a budget shortfall of up to $3 billion in fiscal year 2021, or about 10 percent of the total annual budget (Burness 2020).

In most Tenth District states, fiscal year-to-date tax revenues remained above year-ago levels through March, but March 2020 tax revenues dropped in several states relative to the previous year._ As states delay deadlines for income taxes, and in some cases sales and property taxes, the next few months of data will be difficult to interpret. However, in the months to come, the primary sources of state tax collections are all likely to fall as consumer spending declines, job losses accumulate, and corporate profits decline.

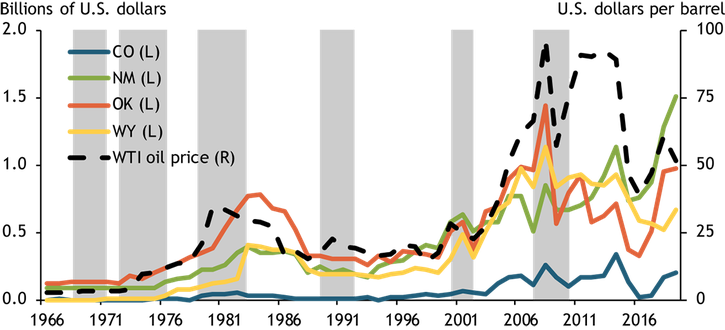

Within the Tenth District, severance taxes—taxes assessed on extracted natural resources such as coal, oil, and natural gas—have already declined sharply. While the broader regional economy held up well through mid-March, oil prices started to fall sharply in January 2020. As a result, severance tax collections are already well below their levels from the previous year. At the national level, severance taxes make up just 1.3 percent of state tax revenue. However, several Tenth District states rely heavily on severance taxes: in New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Wyoming, severance taxes make up 20 percent, 10 percent, and 31 percent of general fund tax revenues, respectively. Through the first nine months of the current fiscal year, severance tax collections fell by 22 percent in Colorado and 27 percent in Oklahoma. Chart 2 shows that severance tax collections have tracked closely with oil prices historically. If this relationship continues, severance taxes could decline dramatically in the coming year in line with the recent fall in the WTI oil price to the $20 to $25 per barrel range in early May 2020.

Chart 2: Real Severance Tax Collections and Oil Prices

Notes: Oil price shown is West Texas Intermediate. Data are through the end of 2019. Gray bars denote NBER-defined recessions.

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, Energy Information Association, and NBER (Haver Analytics).

Strong revenue growth leading up to the current crisis may help states brace for the coming declines in tax revenues. State general fund revenues rose 6.9 percent in fiscal year 2018 and 4.5 percent in fiscal year 2019 (National Association of State Budget Officers 2019). These strong recent gains have helped boost real state tax revenues 46 percent above their levels prior to the Great Recession after adjusting for inflation. States have used some of this revenue to increase their rainy day funds: at the national level, rainy day fund balances have increased from 4.8 percent of annual expenditures in fiscal year 2007 to 8.3 percent in fiscal year 2019. Total balances, which include both rainy day funds and any balance carried forward from the previous fiscal year, were enough to cover 13 percent of annual expenditures (National Association of State Budget Officers 2019). These reserve balances will help states weather the coming downturn, but they are unlikely to be large enough to prevent large budget cuts in the coming years.

As budgets are approved for fiscal year 2021 in the next two months, more details about the specifics of budget cuts within state governments will emerge. However, many governments have already announced layoffs, furloughs, and budget cuts in the current fiscal year. In the next fiscal year, lower tax revenues could lead to lower budgets for universities, less funding for transportation and K-12 education, and freezes on government hiring and salaries. In the longer term, this current crisis is likely to further stress the funding of government pension plans, as contributions will likely be cut and investment returns decline sharply.

Endnotes

-

1

The Tenth District of the Federal Reserve System includes Colorado, Kansas, western Missouri, Nebraska, northern New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Wyoming. Throughout this article, Tenth District data aggregate state-level data for these seven states. Numbers are calculated using data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

-

2

Among Tenth District states, Colorado is estimated to receive $2.23 billion, Kansas $1.25 billion, Missouri $2.38 billion, Nebraska $1.25 billion, New Mexico $1.25 billion, Oklahoma $1.53 billion, and Wyoming $1.25 billion (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities 2020).

-

3

One exception is Oklahoma, where fiscal year-to-date revenues were 0.2 percent lower than revenues last fiscal year. New Mexico data are not available through March, and Wyoming data include sales tax information only.

References

9News. 2020. “External LinkBoulder to Furlough 737 Employees, Citing Economic Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic.” Denver Business Journal, April 14.

Burness, Alex. 2020. “External LinkColorado Lawmakers Bracing for Coronavirus Budget Hit of Up to $3 Billion.” Denver Post, April 9.

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. 2020. “External LinkHow Much Each State Will Receive from the Coronavirus Relief Fund in the CARES Act.” March 26.

National Association of State Budget Officers. 2019. The Fiscal Survey of States: Fall 2019. Washington, DC.

Swanson, Conrad. 2020. “External LinkCoronavirus to Hit Denver’s Revenue Harder than First Year of the Great Recession.” Denver Post. April 14.

Alison Felix is a senior policy advisor at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. Linmei Amaya, a research associate at the bank, helped prepare the article. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.