Traditionally, businesses in need of financing borrow through bank commercial and industrial (C&I) loans or corporate bonds. While these markets still play a pivotal role for business credit, private credit lending by nonbanks has grown at an exponential rate over the past 15 years and now rivals the size of these other traditional debt markets._ This trend has seemingly put banks in competition with private credit funds. However, it has also created a new lending opportunity for banks—banks are increasingly lending to private credit funds themselves (which, in turn, lend to businesses)._ The appeal of this new form of credit intermediation for banks depends crucially on the profitability and riskiness of direct C&I lending compared with indirect C&I lending through private credit funds.

To help compare the profitability of both types of lending, I use bank supervisory data at the loan level to calculate a risk-adjusted return on equity measure, similar to Chernenko, Ialenti, and Scharfstein (2025). While I assume some costs of lending, such as operating and interest expense, are the same, I consider four margins along which bank C&I loans differ from bank loans to private credit funds: interest rate spreads, expected loan losses, credit utilization, and balance sheet costs. First, I incorporate loan-level differences in interest rate spreads from the data to capture variation related to credit risk, illiquidity, and credit demand. Second, I account for expected loan losses using data on predicted default rates and reported loan collateral. Third, I allow for different rates of credit utilization, where unutilized credit is assumed to earn a lower money market return. Last, I account for differences in balance sheet costs stemming from risk-weighted capital requirements. Specifically, I assume that C&I loans require a 100 percent risk weight, whereas loans to private credit funds require a 20 percent risk weight, making C&I more costly on bank balance sheets._

Chart 1 shows that, on average, banks generate a 7.9 percent return on equity from C&I lending (purple bars) compared with a 29.2 percent return on loans to private credit funds (blue bars)._ Taken at face value, these results suggest that indirect lending through private credit funds is much more profitable for banks than direct C&I lending. This finding is consistent with other types of bank lending. For example, in the U.S. mortgage market, banks often find it more profitable to indirectly fund mortgage loans through warehouse lending to nonbank originators or through the purchase of mortgage-backed securities (MBS)._

Chart 1: Bank loans to private credit funds offer higher risk-adjusted returns on average

Notes: Loan-level data are partitioned by the borrower being either a non-financial corporate borrower (labeled “C&I loans”) or a private credit fund (labeled “loans to private credit funds”). The sample is restricted to revolving lines of credit with floating interest rates.

Sources: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and author’s calculations.

Chart 2 shows the main drivers of these loans’ profitability by decomposing the difference in return on equity between the two types of loans into the four separate margins. The decomposition emphasizes that balance sheet costs (due to the lower risk weight treatment of loans to private credit funds) are currently the main driver of differences in return on equity. Loan-level evidence on risk characteristics is generally consistent with this lower risk weight for private credit funds. For example, the average bank C&I loan has a 1 percent predicted rate of default, compared with 0.2 percent for loans to private credit funds. In addition, loan collateral gives the average C&I loan an 82 percent recovery rate, compared with an 85 percent recovery rate for loans to private credit funds.

Chart 2: Lower bank balance sheet costs drive profitability differences between private credit and C&I loans

Note: “Return on equity decomposition” shows how the four factors affect a bank’s loan-level return on equity.

Sources: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and author’s calculations.

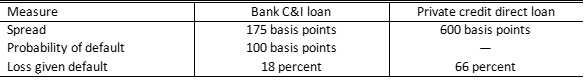

While bank lending to private credit funds appears to be more profitable than traditional C&I lending, the ultimate benefit to banks depends on whether these two types of lending are substitutes or complements from the bank’s perspective. Are banks simply lending to their usual loan customers indirectly through private credit funds, or are the loans to private credit funds reaching an altogether different set of borrowers? Table 1 compares price and risk characteristics between bank C&I loans and loans made directly by private credit funds. The data suggest that private credit funds are lending into markets with much higher credit risk, as indicated by higher loan spreads and higher loss given default._ In other words, bank lending to private funds is a fundamentally different form of business lending, where banks are not competing for their usual loan customers but rather reaching a new set of higher-risk customers through indirect lending to private credit funds._ Moreover, because banks are lending at the fund level, they are not directly exposed to the higher credit risk of individual private credit loans. As a result, banks treat loans to private credit as relatively low risk and well collateralized.

Table 1: Private credit funds make riskier loans compared with a typical bank C&I loan

Notes: “Spread” measures additional loan interest charged above a base index rate, which is usually SOFR. “Probability of default” is an internal bank measure and thus not observed for private credit direct loans. “Loss given default” measures the total share of loan principal lost in the event of default and thus accounts for loan collateral.

Sources: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, PitchBook LCD, and KBRA Analytics (accessed via Cai and Haque 2024).

All in all, this analysis shows that the growth of the private credit industry has offered banks a new, profitable form of indirect lending, positioning the two lenders more as partners than competitors. While private credit funds and banks both lend to businesses, loan pricing suggests that they do not directly compete for the same set of borrowers; instead, bank lending complements private credit lending. However, this landscape may be changing: Recent evidence suggests private credit lenders are increasingly lending to large, public, and investment-grade businesses._ Such a shift in target borrowers would necessarily put the private credit market in direct competition with bank loans and the corporate bond market, with implications for both bank pricing and financial stability.

Endnotes

-

1

Private credit generally refers to nonbank business lending, which is performed by private debt funds or business development companies (BDCs) regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

-

2

See, for example, Berrospide and others (2025) and Levin and Malfroy-Camine (2025) for an in-depth summary of linkages between banks and private credit funds.

-

3

This assumption is consistent with those used by Chernenko and others (2025) and is based on the fact that collateral for loans to private credit funds are often stored in bankruptcy-remote special-purpose vehicles (SPVs) that allows them to qualify as securitizations, which earn a lower risk-weight compared with a typical C&I loan.

-

4

Specifically, the return on equity for a loan is computed as ([1 − tax] / capital)(r + spread – E[Losses] – OpExp – (1 – capital) * funding cost), where the tax rate is set at 0.25, r = 0.053 is the assumed base money market rate, spread is the loan interest rate spread above the base rate, E[Losses] is the expected losses combination of default probability and loss given default, OpExp = 0.004 is the loan operating expense set from estimates from Corbae and D’Erasmo (2021), and funding cost is the debt interest expense of funding a loan and assumed equal to the base rate r. Last, capital measures the percentage of the loan that must be funded through equity. It is the product of a target capital ratio, which I assume to be 12 percent, and a risk weight.

-

5

See Jiang (2023), Drechsler and others (2024), and Acker, An, and Pandolfo (2025).

-

6

A more realistic loan-level comparison may be achieved by looking at the bank syndicated loan market, which generally caters to a riskier group of corporate borrowers. But even in this market, loan interest rate spreads do not come near those set by private credit lenders. For example, see Liu and Pogach (2017).

-

7

Fillat and others (2025) argue that these large loan spreads could also be driven by borrower demand for private credit loans, which offer more flexibility. While this demand is likely an important contributing factor, it is unclear whether borrower demand could justify such a large difference in loan spreads when borrowers consider loans from banks compared with a private credit fund.

-

8

For example, see Saeedy (2025).

References

Acker, Chris, Phillip An, and Jordan Pandolfo. 2025. “Interest Rates and Nonbank Market Share in the U.S. Mortgage Market.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Review, vol. 110, no. 1.

Berrospide, Jose, Fang Cai, Siddhartha Lewis-Hayre, and Filip Sikes. 2025. “External LinkBank Lending to Private Credit: Size, Characteristics, and Financial Stability Implications.” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, FEDS Notes, May 23.

Cai, Fang, and Sharjil Haque. 2024. “External LinkPrivate Credit: Characteristics and Risks.” Board of the Governors of the Federal Reserve System, FEDS Notes, February 23.

Chernenko, Sergey, Robert Ialenti, and David Scharfstein. 2025. “External LinkBank Capital and the Growth of Private Credit.” SSRN, January 17.

Corbae, Dean, and Pablo D’Erasmo. 2021. “External LinkCapital Buffers in a Quantitative Model of Banking Industry Dynamics.” Econometrica, vol. 89, no. 6, pp. 2975–3023.

Drechsler, Itamar, Alexi Savov, Philipp Schnabl, and Dominik Supera. 2024. “Monetary Policy and the Mortgage Market.” Reassessing the Effectiveness of Monetary Policy. Proceedings of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Policy Symposium, Jackson Hole, WY, August 22–24, pp. 357–436.

Fillat, Jose L., Mattia Landoni, John D. Levin, and J. Christina Wang. 2025. “External LinkCould the Growth of Private Credit Pose a Risk to Financial System Stability?” Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Current Policy Perspectives, no. 25-8, pp. 1–8.

Jiang, Erica Xuewei. 2023. “External LinkFinancing Competitors: Shadow Banks’ Funding and Mortgage Market Competition.” Review of Financial Studies, vol. 36, no. 10, pp. 3861–3905.

Levin, John D., and Antoine Malfroy-Camine. 2025. “External LinkBank Lending to Private Equity and Private Credit Funds: Insights from Regulatory Data.” Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Supervisory Research and Analysis Note, no. 2025-02, February 5.

Liu, Edith X., and Jonathan Pogach. 2017. “External LinkGlobal Banks and Syndicated Loan Spreads: Evidence from U.S. Banks.” FDIC Center for Financial Research, working paper no. 2017-01.

Saeedy, Alexander. 2025. “External LinkJamie Dimon Says Private Credit Is Dangerous—and He Wants JPMorgan to Get In on It.” Wall Street Journal, July 13.

Jordan Pandolfo is an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.