The coronavirus-induced plunge in the U.S. economy may further strain state and local public pensions in the years to come. Even before the pandemic began, pension funding had not completely recovered from the 2001 and 2007–09 recessions. The two major sources of state and local pension fund revenues, investment returns and contributions from state and local government employers, both took hits during these recessions (NASRA 2020)._ These drops in revenue led to lower pension funding and, in many cases, changes to pension plan structures that lasted well after the economy had fully recovered.

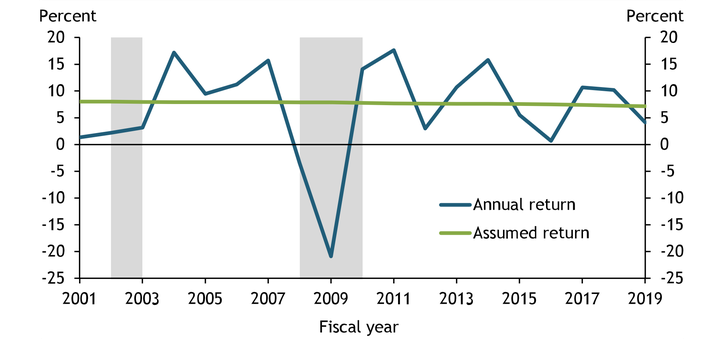

State and local pension plans allocate over two-thirds of their more than $4.4 trillion in assets to volatile equity markets and alternative investments, making them vulnerable to potentially large revenue declines during downturns. Before the 2001 recession, state and local pension plans assumed, on average, that their portfolios would earn 8 percent annually over the long term. However, Chart 1 shows that annual returns vary considerably. Recessions, for example, can have an immediate and significant negative effect on pension returns. From fiscal year 2001 to 2003, returns equaled 1 to 3 percent annually, well below the assumed return. Investments fared much worse during the 2007–09 recession, with portfolio returns dropping 3.5 percent in fiscal year 2008 and 20.9 percent in 2009.

Chart 1: Actual and Expected Annual Investment Returns for State and Local Public Pensions

Note: Gray bars denote National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER)-defined recessions.

Sources: Center for Retirement Research (CRR) at Boston College, Center for State and Local Government Excellence (SLGE), the National Association of State Retirement Administrators (NASRA), and NBER (Haver Analytics).

Although investment returns have performed better in the current recession so far, they remain below longer-term assumed returns. On average, state and local pension plans assumed their portfolios could earn 7.1 percent annually over the long term in their fiscal year 2019 financial statements._ However, the median annual return for public pension funds was just 3.2 percent in fiscal year 2020, which ended June 30 for most pension funds (Gillers 2020).

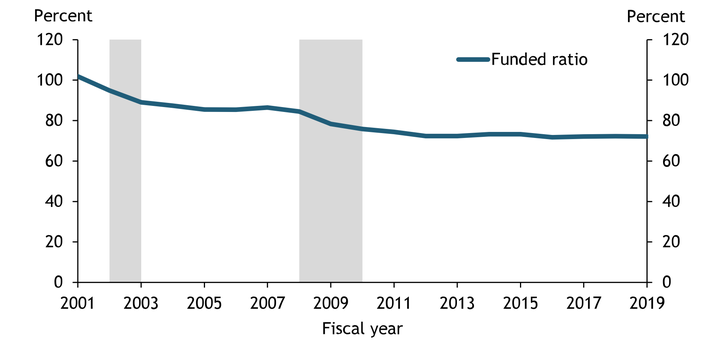

If investment returns fail to keep up with assumed returns in the longer run, overall pension funding ratios will decline. Funded ratios are calculated by dividing a pension plan’s total assets by its liabilities—the approximate amount of money needed to cover future payments. A funded ratio of 100 percent indicates that pension funds have enough assets (assuming actual investment returns equal assumed returns and that other model assumptions hold) to cover expected future pension liabilities. A funded ratio below 100 percent indicates a shortfall is likely. Chart 2 shows that following the 2001 recession, the average funded ratio of state and local pension funds fell from 101.9 percent in fiscal year 2001 to 89 percent in fiscal year 2003. By the time the Great Recession started in 2007, the funded ratio had not fully recovered; the ratio fell from 86.5 percent in fiscal year 2007 to 72.4 percent in fiscal year 2012 and has remained relatively steady since.

Chart 2: Aggregate Funded Ratios for State and Local Pension Funds

Chart 2: Aggregate Funded Ratios for State and Local Pension Funds

Note: Gray bars denote NBER-defined recessions.

Sources: CRR, SLGE, NASRA, and NBER (Haver Analytics).

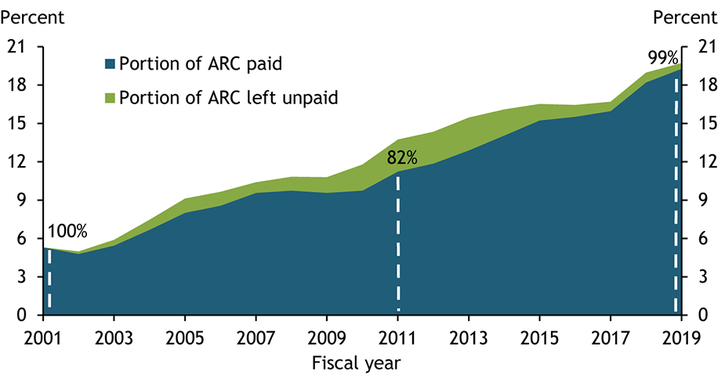

Although lower investment returns played a large role in reducing funded ratios, insufficient employer contributions also put downward pressure on these ratios. Economic downturns frequently challenge state and local government finances, making it difficult for these governments to fully fund pension plans. For pensions to be fully funded, government employers and employees must pay enough annually to cover the present value of expected future benefits as well as any gap between the current and 100 percent funded ratios. This amount is called the annual required contribution (ARC). Chart 3 shows that the ARC as a share of government payrolls has increased over time, roughly inverse to the decline in funded ratios shown in Chart 2.

Chart 3: Annual Required Contribution as a Percent of Payroll and Portion of ARC Paid

Note: Dashed lines and percentage labels indicate the percent of the ARC that was paid in 2001, 2011, and 2019.

Sources: CRR, SLGE, and NASRA.

Chart 3 also shows that the portion of the ARC that government employers and employees paid decreased after the last two recessions. In 2001, employers and employees combined paid 100 percent of the ARC, essentially keeping pension plans fully funded. Over the next decade, however, this percentage fell. In 2011, only 82 percent of the ARC (blue-shaded region) was paid. In other words, following the last two recessions, funded ratios fell due to both weak investment returns and insufficient employer and employee contributions.

Over the past few years, state and local governments have worked to increase their contributions to public pensions: in fiscal year 2019, contribution rates reached 99 percent of the ARC. This increase is particularly notable given the significant increase in the ARC as a share of government payrolls. However, the current recession is likely to unwind these gains. State and local governments are already facing significant budget shortfalls which will likely lead to lower contribution rates in the years to come. For example, Colorado has already suspended its direct distribution to the public employees’ retirement association for fiscal year 2021.

If the current crisis leads to a decline in pension funded ratios, state and local governments may be forced to make changes to pension plans as they look for ways to strengthen funding levels and reduce the odds of a future shortfall in pension funding. In the aftermath of the Great Recession, state and local governments tried to preserve the solvency of pension plans by making structural changes to plans. In many cases, these structural changes led to higher costs and lower benefits for state and local employees. For example, following the Great Recession, a majority of states increased the amount employees must contribute annually to pension plans. Many states also lowered the benefit of pension plans by changing the formula for the annual pension benefit, reducing or eliminating cost-of-living adjustments, or by increasing the age or years of service needed to collect pension benefits. Almost half of states also introduced some type of risk-sharing element to their pension structures in which employees’ contribution rates or benefit levels could be automatically adjusted depending on factors affecting the health of the pension plan, such as funding levels, investment returns and inflation (Brainard and Brown 2018).

Although the risk-sharing elements of pension plans introduced after the Great Recession may help mitigate the decline in pension funding during the current crisis, the sharp decline in funding ratios during the 2001 and 2007 recessions highlight that economic downturns pose significant risks to pension funding. In particular, investment returns fell short of longer-run assumed returns during the previous two recessions, leading to sharp drops in pension funding ratios. In addition, drops in state and local government revenues during the previous two recessions left governments without enough money to fully fund pensions, which put additional downward pressure on funding. Should the current deep recession be protracted, state and local governments may face difficult decisions about how to preserve the solvency of pension plans, which may alter the benefits and structures of their plans in the longer run.

Endnotes

-

1

From 1989 to 2018, investment earnings made up 63 percent of pension fund revenues, while employer contributions made up 26 percent and employee contributions made up 11 percent.

-

2

State and local governments reduced the assumed investment return from 8 percent in 2001 to 7.1 percent in 2019. In fiscal year 2019, about 47 percent of pension plan assets were invested in equities, 23 percent in fixed income, 9 percent in private equity, 9 percent in real estate, 7 percent in hedge funds and 5 percent in cash, commodities, and miscellaneous alternatives.

References

Brainard, Keith, and Alex Brown. 2018. “External LinkSignificant Reforms to State Retirement Systems.” National Association of State Retirement Administrators (NASRA), Spotlight On, December.

Gillers, Heather. 2020. “External LinkBeleaguered Public Pension Funds Make Record Gains in Second Quarter.” Wall Street Journal, August 4.

NASRA (National Association of State Retirement Administrators). 2020. “External LinkNASRA Issue Brief: State and Local Government Contributions to Statewide Pension Plans: FY 18.” NASRA, April.

Alison Felix is a senior policy advisor at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. Samantha Shampine, a research associate at the bank, helped prepare the article. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.