Consumer sentiment—a measure of how consumers are feeling about the economy—draws consistent attention from policymakers and economic forecasters. Information about consumer sentiment collected in surveys such as the University of Michigan’s Survey of Consumers or The Conference Board’s Consumer Confidence Survey is often viewed as a predictor of the direction of household spending. These surveys are published more frequently than data on real personal consumption expenditures (PCE) and contain information about future purchases (for example, plans of future household purchases), which might be particularly useful when predicting future spending growth.

Recent data suggest consumer sentiment has been declining for the past several months, signaling a potential slowdown in spending. However, most measures of actual spending, such as core retail sales and PCE, have remained relatively stable. This discrepancy raises the question of how useful consumer attitudes are in predicting actual spending.

To evaluate whether measures of consumer sentiment improve consumer spending forecasts, we first establish a baseline that relies only on current and past values of spending and income growth._ Next, we generate forecasts from models that augment this baseline model by including current and past values of consumer attitudes from either the University of Michigan, The Conference Board, or both. Lastly, we take the average of each of these individual forecasts to generate the “sentiment-augmented” model._ Averaging forecasts not only simplifies our discussion, but typically also leads to greater precision (see, for example, Wright 2003 and Steel 2020).

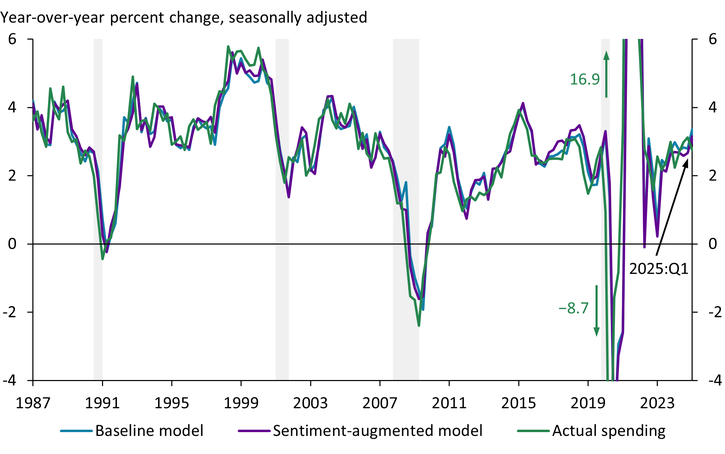

Chart 1 shows that forecasts of household spending generated from our baseline and sentiment-augmented models track each other closely. The chart plots one-quarter-ahead forecasts for each model and highlights that over the past 30 years, predictions using only official data are quite similar to those using both official data and consumer sentiment. The baseline model (blue line) and sentiment-augmented model (purple line) both track each other and actual spending (green line) fairly well. Additionally, although it was difficult to forecast spending growth in 2020 at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the accuracy of both types of models has improved over the past two years.

Chart 1: One-quarter-ahead consumption growth forecasts look similar with or without consumer sentiment

Note: Shaded bars denote National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER)-defined recessions.

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), University of Michigan, The Conference Board, NBER (Haver Analytics), and authors’ calculations.

We reach the same conclusion when plotting forecast horizons of two, three, and four quarters ahead as for one-quarter-ahead forecasts. Naturally, the precision of any type of model decreases as the forecast horizon increases. However, we still find similar forecast performance, at a given horizon, between our baseline and sentiment-augmented models—in line with earlier studies that have reached similar conclusions._

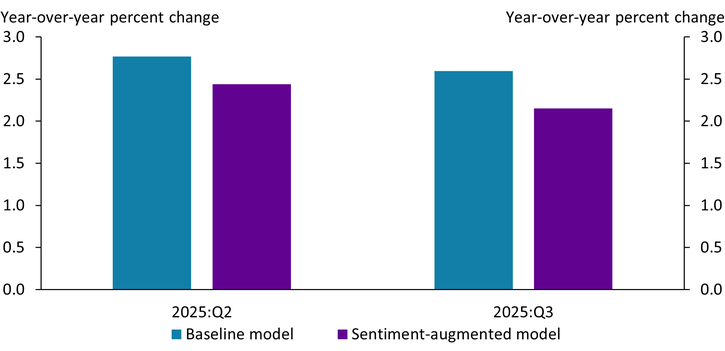

Consistent with evidence from the prior 30 years, the near-term outlook for spending growth looks similar regardless of whether we account for the recent weakening in consumer sentiment. Chart 2 shows that spending forecasts are within half a percentage point of each other for the next two quarters of 2025. Given the historical accuracy of the models we consider and the volatility in actual data, this difference is fairly modest. For reference, both forecasts from a year ago predicted spending growth of around 2.7 percent in the second quarter of 2024—within 0.3 percentage points of this year’s Q2 forecast. Neither forecast suggests a sharp contraction in consumer spending.

Chart 2: Spending growth predictions in 2025 only modestly differ between the baseline and sentiment-augmented models

Sources: BEA, University of Michigan, The Conference Board, and authors’ calculations.

We find that consumer sentiment data have not substantially improved forecasts of consumer spending growth beyond what official data already indicate. At the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) press conference in May, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell noted “the link between sentiment data and consumer spending has been weak. It’s not been a strong link at all…it wouldn’t be the case that we’re looking at [consumer sentiment] and just completely dismissing it. But it’s another reason to wait and see” (2025). In other words, although consumer sentiment data remain useful for gauging household attitudes toward the economy, forecasters should expect limited deviations from what baseline indicators provide.

Download Materials

Endnotes

-

1

Like Bram and Ludvigson (1998), we estimate a linear regression of one-quarter-ahead real personal consumption expenditures growth (PCE) against the current and past three quarters of real PCE growth and real labor income growth. We estimate the model using data from 1967 to 2019 to prevent our forecasting model from being overly influenced by the atypical swings in spending growth during the pandemic. Labor income is defined as wages and salaries plus transfers minus personal contributions for social insurance. All growth rates are measured relative to the same quarter a year prior (that is, year-over-year).

-

2

More specifically, we average forecasts across six models that differ in what consumer sentiment measure is used: (i) consumer sentiment from the University of Michigan, (ii) consumer confidence from The Conference Board, (iii) both consumer sentiment and consumer confidence, (iv) consumer expectations from the University of Michigan, (v) consumer expectations from The Conference Board, and (vi) consumer expectations from both the University of Michigan and The Conference Board.

-

3

Carroll, Fuhrer, and Wilcox (1994) find that consumer sentiment from the University of Michigan adds little additional information to forecasts of consumer spending. By contrast, Bram and Ludvigson (1998) find that consumer confidence from The Conference Board does provide some additional information above and beyond standard measures like prior spending and labor income. However, this observation appears to be mostly true in the 1980s, as forecast accuracy diminishes by 1996, when their analysis ends.

References

Bram, Jason, and Sydney Ludvigson. 1998. “External LinkDoes Consumer Confidence Forecast Household Expenditure? A Sentiment Index Horse Race.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Economic Policy Review, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 59–78.

Carroll, Christoper D., Jeffrey C. Fuhrer, and David W. Wilcox.1994. “External LinkDoes Consumer Sentiment Forecast Household Spending? If So, Why?” American Economic Review, vol. 84, no. 5, pp. 1397–1408.

Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). 2025. “External LinkFOMC Press Conference, May 7, 2025.”

Steel, Mark F. J. 2020. “External LinkModel Averaging and Its Use in Economics.” Journal of Economic Literature, vol. 58, no. 3, pp. 644–719.

Wright, Jonathan H. 2003. “External LinkForecasting U.S. Inflation by Bayesian Model Averaging.” Board of Governors, International Finance Discussion Paper, no. 780.

José Mustre-del-Río is an assistant vice president and economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. Jalen Nichols is a research associate at the bank. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.