Growth in agricultural real estate values surged during 2021 and 2022 alongside historically high farm incomes and low interest rates (Kauffman and Kreitman 2023). In 2023, farmland values held firm while interest rates increased alongside benchmark rates. Together, strong real estate valuations and higher interest rates have pushed up interest expenses on land loans, potentially squeezing profitability for crop producers.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), agricultural real estate accounts for more than 80 percent of U.S. farm sector assets, and real estate debt makes up more than 70 percent of all liabilities for the sector. Thus, an increase in interest expenses on land debt is likely to have a substantial influence on the sector. The steep increase in interest expenses is likely to be acutely burdensome for owner-operated farms with high leverage and may deter some farmers from refinancing or taking on new debt.

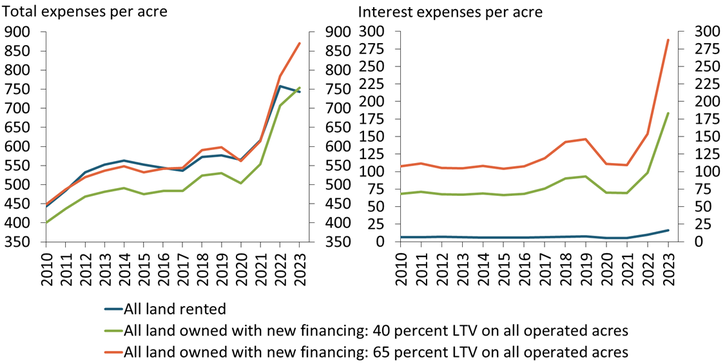

Notably, these increases in financing costs have occurred at a time when farm operational costs have declined. The blue line in the left panel of Chart 1 shows that total expenses for an average corn and soybean farm without new land debt stabilized in 2023._ The slight decline in farm expenses reflects a decline in the costs of many key inputs such as fuel and fertilizer following two years of substantial increases. However, the green and orange lines show that total expenses for an average farm with new land debt continued to rise.

The right panel of Chart 1 confirms that financing costs pushed up total expenses for farms with land debt. Interest expenses per acre grew during 2023 alongside higher interest rates, particularly for operations with large amounts of new debt. The green line shows that a farm with new or refinanced land debt totaling 40 percent of the value of all operated acres—that is, a 40 percent loan-to-value (LTV) ratio—saw an increase in interest expenses of nearly $100 per acre from 2022 to 2023. The orange line shows that a farm with a 65 percent LTV had an increase of more than $125 per acre.

Chart 1: Larger interest payments increased total expenses considerably for operations with high amounts of new land debt in 2023

Sources: USDA, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, and author’s calculations.

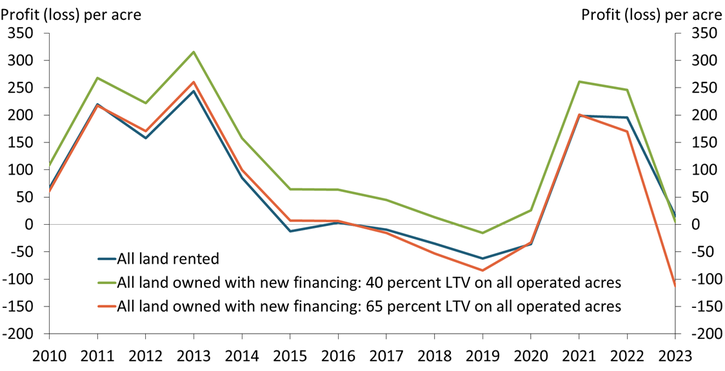

Profit opportunities thinned for all crop producers during 2023 alongside a moderation in crop prices, but those with large amounts of land debt could face additional pressures. The green line in Chart 2 shows that in 2023, a farm with a new loan with a 40 percent LTV ratio on all operated acres would likely break even selling crops at average prices, similar to a farm that rents all operated acres and has no land debt (blue line)._ Moreover, the orange line shows that a farm with a new loan with a 65 percent LTV ratio on all operated acres would likely incur losses. According to the USDA’s Agricultural Resource Management Survey, around 45 percent of U.S. corn and soybeans farms owned all land operated in 2022, around 40 percent owned a portion of land operated but rented the remainder, and about 15 percent rented all land operated. Farms that own land can have varying debt levels and repricing schedules that influence exposure to higher interest costs. Farms with higher leverage and higher shares of newly financed land debt are likely to have the most pressure on their profit margins.

Chart 2: Farms financing higher shares of operated acres at recent interest rates are notably more exposed to losses

Sources: USDA, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, and author’s calculations.

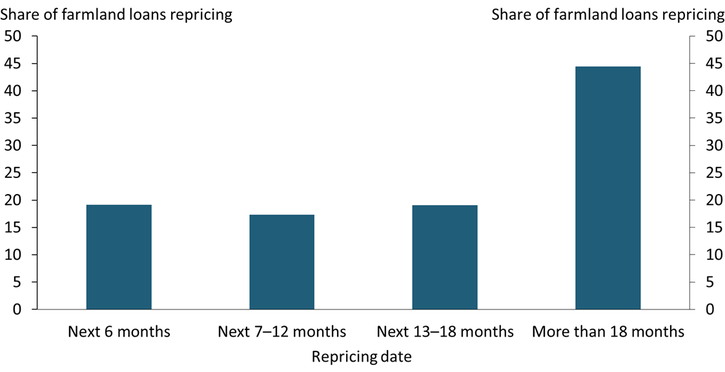

Higher interest costs are likely to weigh on both new land purchases and the incomes of borrowers refinancing existing debt. According to the Survey of Agricultural Credit Conditions, near-term repricing schedules are common on debt secured by farm real estate at commercial agricultural banks. Indeed, Chart 3 shows that commercial banks in the survey are, on average, scheduled to reprice about one-fifth of farmland loans every six months. More than half of farmland loans will assume a new interest rate over the next 18 months. Borrowers refinancing debt secured prior to 2022 will face considerably higher interest payments than when the loan was originated.

Chart 3: A sizeable share of farmland loans at commercial banks have been recently repriced or are scheduled to be repriced in the coming months

Notes: Bars show average response across all survey participants. Respondents were asked approximately what percent of farmland loans in their bank’s portfolio were scheduled to reprice in the next six months, the next seven to 12 months, the next 13 to 18 months or more than 18 months into the future.

Sources: Federal Reserve Banks of Kansas City, Minneapolis, Richmond, and St. Louis.

Reducing financing costs could require producers to have sizeable amounts of cash on hand for down payments. The average interest rate on farmland loans has more than doubled since the beginning of 2022 and increased loan payments considerably. For new land purchases, the amount of funds needed to reduce debt balances and lower loan payments has increased alongside strong growth in farm real estate values. For farms refinancing existing debt, higher interest payments could materially reduce repayment capacity and may require paying down a portion of outstanding debt.

Together, these results suggest that in the current interest rate environment, crop producers with new or newly refinanced land debt may struggle to reach profitability without strong equity positions, large cash down payments, or an improvement in agricultural economic conditions. Considerable strength in farm income in recent years has bolstered working capital and could alleviate the debt burden for some operators refinancing existing land debt. However, high financing costs could reduce demand for newly financed agricultural real estate purchases and be especially burdensome for highly leveraged crop producers.

Download Materials

Endnotes

-

1

All scenarios assume the operation is a 50/50 corn and soybean farm that finances 50 percent of operating expenses at the beginning of the year and pays interest and principal on operating debt in full at year-end. Rent is equal to the opportunity cost of land reported in the costs and return estimates. Land values are the national average value of cropland during each year and land debt is a 30-year loan with average annual interest rates and equal annual payments. Interest expense on land debt is the interest paid on the first loan payment.

-

2

All scenarios assume the operation is a 50/50 corn and soybean farm that finances 50 percent of operating expenses at the beginning of the year and pays interest and principal on operating debt in full at year-end. All scenarios also assume national average crop yields and average crop prices at harvest. Rent is equal to the opportunity cost of land reported in the costs and return estimates. Land values are the national average value of cropland during each year, and land debt is a 30-year loan with average annual interest rates and equal annual payments.

Reference

Kauffman, Nate, and Ty Kreitman. 2023. “External LinkCredit Conditions and Farmland Values on Solid Footing as Farm Economy Moderates.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Ag Finance Update, May 24.

Ty Kreitman is an associate economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.