During the 2000s, both debit card transactions and interchange fees charged to merchants increased sharply in the United States, in part due to routing limitations and exclusivity agreements between card networks and issuers. To address growing fees and limited routing options, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System implemented Regulation II in 2011. Regulation II capped debit card interchange fees received by large issuers (but not smaller “exempt” issuers), prohibited network exclusivity arrangements, and prohibited limitations on merchants’ routing choices.

In this article, Fumiko Hayashi examines whether the prohibitions on exclusivity arrangements and routing limitations helped reduce exempt interchange fees charged to small merchants for in-person debit card transactions. She finds that while some networks reduced these fees for certain merchant categories, other networks either increased or did not change their fees. Moreover, the size of the interchange fee increases was generally much greater than the size of the reduction. Her results suggest that exempt interchange fees did not decrease broadly for small merchants after Regulation II.

Introduction

During the 2000s, both the number of debit card transactions and the level of interchange fees charged to merchants increased sharply in the United States. One possible reason that interchange fees increased is that merchants were limited in their ability to route transactions to preferred debit card networks, due to exclusivity agreements between card networks (who set interchange fees) and issuers (who collect them) as well as to priority routing that issuers imposed. A section of the Dodd-Frank Act passed by Congress in 2010 included requirements to address growing fees and limited routing options, which the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System implemented in 2011 through Regulation II. Regulation II has three main provisions: 1) a cap on debit card interchange fees received by large, “regulated” issuers (but not smaller, “exempt” issuers); 2) a prohibition on network exclusivity arrangements between networks and issuers; and 3) a prohibition on limiting merchants’ ability to route transactions over any network available for a given debit card.

Although the first provision of Regulation II does not apply to smaller, “exempt” issuers—which collectively account for about 35 percent of all debit card transactions—the second and third provisions could reduce interchange fees received by exempt issuers by increasing competition among card networks for merchants. According to data collected by the Federal Reserve Board, since Regulation II was implemented, the average exempt interchange fee has decreased slightly for single-message networks (those that typically authenticate transactions with a PIN, such as Interlink, Maestro, STAR, NYCE, PULSE, and others) but increased for dual-message networks (those that typically authenticate transactions with a signature, such as Visa, Mastercard, and Discover). However, these averages may not reflect the exempt interchange fees paid by small merchants. Many small merchants have limited means to negotiate with card networks or easily identify the lowest-cost network for them, restricting their ability to put downward pressure on exempt interchange fees.

In this article, I examine whether debit card networks reduced the exempt interchange fees charged to small merchants for in-person transactions after Regulation II. I find that although some networks reduced exempt interchange fees for at least one of the four major merchant categories for in-person transactions (grocery, general retail, gas station, and quick-service restaurant), other networks either increased or did not change their fees. Moreover, the size of the interchange fee increase was generally much greater than that of the interchange fee reduction. These results suggest that exempt interchange fees did not decrease broadly for many small merchants after Regulation II.

Section I explains Regulation II and exempt interchange fee structures. Section II examines which networks reduced, did not change, or increased exempt interchange fees charged to small merchants. Section III discusses possible reasons why exempt interchange fees charged to small merchants did not decline and even increased in some networks.

I. Regulation II and Exempt Interchange Fee Structures

In the United States, each debit card transaction is processed on one of two types of networks. Single-message networks traditionally authenticate cardholders through a PIN and use a single message both to authorize the transaction and to clear the payment. Dual-message networks, which use the same infrastructure as credit card networks, traditionally authenticate cardholders with a signature and process the transaction using two separate messages—one for transaction authorization and one for payment clearing (Hayashi, Sullivan, and Weiner 2003).

For each debit card transaction, the merchant pays network fees, processing fees, and an interchange fee. Network fees (such as a switch fee and an assessment fee) are paid to the card network, whether single- or dual-message. Processing fees are paid to the merchant acquirer (the merchant’s bank) and processor, which perform functions such as linking merchants to card networks and crediting merchant accounts for sales on card transactions. The interchange fee is paid to the issuer (the bank that issues the debit card) but set by the network that processes the transaction. The interchange fee accounts for the largest share of the overall charges levied on merchants per transaction. For example, the Food Marketing Institute (2011) estimates that interchange fees make up roughly 85 percent of supermarkets’ merchant fees.

During the 2000s, the use of debit cards increased more than fourfold in the United States, and by 2009, they became the most-used noncash retail payment method (Federal Reserve System 2011). At the same time, the fees merchants were charged to process debit card transactions on both single- and dual-message networks grew sharply. From 2004 to 2010, the average fees charged to merchants rose from 0.61 percent of a transaction’s value to 0.72 percent on single-message networks and from 1.39 percent of a transaction’s value to 1.85 percent on dual-message networks (Hayashi 2012).

Although merchants could theoretically access about 15 debit card networks in the late 2000s, they had limited ability to route transactions to preferred networks. Some card networks and issuers were engaged in network exclusivity arrangements, wherein the issuers restricted transactions on their debit cards to a dual-message network and an affiliated single-message network. Furthermore, many issuers adopted priority-routing settings, wherein the issuers determined which networks would process transactions for their cards and imposed the routing on merchants.

In July 2011, the Federal Reserve Board adopted Regulation II, which implements the requirements of the Durbin Amendment to the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. Regulation II contains three main provisions. The first provision caps interchange fees and sets the maximum permissible fee at $0.21 plus 0.05 percent of the value of the transaction, with a $0.01 fraud prevention adjustment for eligible large issuers._ The cap applies only to large issuers, defined as those that have assets of $10 billion or more together with their affiliates. Smaller issuers are exempt from this fee cap._ The second provision prohibits network exclusivity arrangements by requiring all issuers to enable at least two unaffiliated networks to process a debit card transaction._ The third provision prohibits issuers and networks from inhibiting merchants’ ability to route a transaction over any network enabled to process the transaction.

Although most networks set interchange fees received by large issuers at or just below the regulatory cap after Regulation II, they continued to freely set interchange fees received by exempt issuers. Exempt interchange fees are complex and typically vary by merchant category—for example, the same network may set different interchange fees for grocery purchases relative to general retail or gas station purchases. In addition, many networks offer volume discounts on interchange fees to large merchants that generate a sufficiently large number of transactions for the network. Some networks have had preferred-issuer programs since the early 2010s, through which they offer higher “premium” interchange fees to issuers that commit to a specific volume of transactions on the given network. Some networks have different interchange fees based on whether the card is a non-prepaid or prepaid debit card. Some exempt interchange fees are fixed fees, while others are proportional to the transaction value, and still others combine a fixed component with a proportional component.

According to data collected by the Federal Reserve Board, the average exempt debit card interchange fee has been very different between the two types of networks. For single-message networks, the average exempt interchange fee decreased from $0.31 per transaction in 2011 to $0.27 in 2023, and fees as a share of the average transaction value also declined from 0.72 percent to 0.68 percent (Federal Reserve Board 2024). In contrast, for dual-message networks, the average exempt interchange fee increased from $0.51 per transaction in 2011 to $0.62 in 2023, but fees as a share of the average transaction value actually declined from 1.44 percent to 1.41 percent. This decline is due to a significant increase in the average value of an exempt transaction for dual-message networks over this period, from $36 to $44._

These averages, however, may not reflect the exempt interchange fees paid by small merchants. Compared with large merchants, small merchants may have more limited means to easily identify the lowest-cost networks and therefore may not be able to put downward pressure on exempt interchange fees through their routing choices. In addition, while large merchants’ higher volume of debit card transactions may help them negotiate lower fees with card networks, small merchants may have less power to negotiate. Because of these differences, exempt interchange fees paid by small merchants may have increased even if those paid by large merchants decreased.

II. Changes in Exempt Interchange Fees Charged to Small Merchants

I examine how exempt interchange fees charged to small merchants have changed from October 2011, when Regulation II became effective, to August 2024 across 13 networks—three dual-message networks and 10 single-message networks—that have operated during this entire period within the United States._ Some networks share the same owner. Each of the three dual-message networks owns a single-message network: Discover owns PULSE, Mastercard owns Maestro, and Visa owns Interlink. Furthermore, two large payment processing firms own multiple single-message networks: Fiserv owns ACCEL and STAR, and FIS owns Culiance and NYCE._ I use each network’s interchange fee schedule made available by card networks, merchant acquirers, and processors.

I focus on in-person transactions for small merchants that do not qualify for volume discounts; due to a lack of data, I cannot examine exempt interchange fees charged to large merchants._ I also do not examine exempt interchange fees charged to merchants for remote transactions, such as online, telephone, or mail-order transactions—partly due to a lack of data and partly because at the time Regulation II was implemented, many single-message networks did not have the capability to process remote transactions.

To assess how exempt interchange fees charged to small merchants have changed over time, I calculate the interchange fee assessed for a transaction in October 2011 and August 2024 in each of four major merchant categories: grocery, general retail, gas station, and quick-service restaurant. To calculate the interchange fees for grocery stores, general retail merchants, and gas stations, I use a $40 transaction, which is roughly the average value of a debit card transaction since 2009 (Federal Reserve Board 2024). For quick-service restaurants, where the average value of a transaction is generally small, I use a $10 transaction. Each network’s interchange fee schedule typically includes these four merchant categories, and some networks set multiple exempt interchange fees for a given merchant category. For example, several single-message networks have preferred-issuer programs, setting a higher premium interchange fee for participating issuers. Some networks also set a higher interchange fee for prepaid debit cards than for non-prepaid debit cards. In these cases, I compare the lowest and the highest interchange fees between the two points of time for a given merchant category.

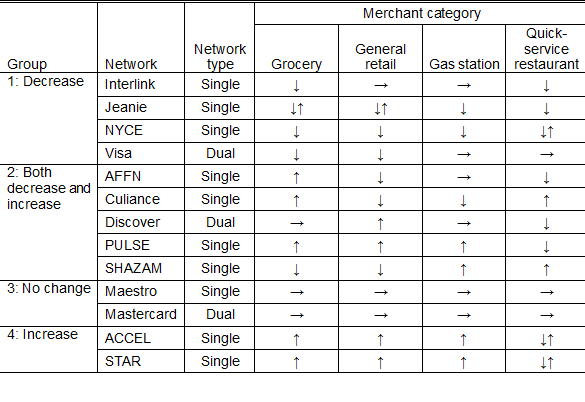

Table 1 divides the 13 networks into four groups based on how they changed their exempt interchange fees for small merchants from 2011 to 2024. The first group of four networks is the “decrease” group, as these networks generally decreased interchange fees over this period. More precisely, these four networks decreased interchange fees for at least one merchant category (denoted as “↓” in Table 1), and in the other merchant categories, they either (i) did not change interchange fees (denoted as “→”), or (ii) both decreased and increased interchange fees within a given category (denoted as “↓↑”). For example, Jeanie decreased a non-premium interchange fee but increased a premium interchange fee for grocery stores. Two networks owned by Visa (Interlink and Visa) decreased interchange fees for one or two merchant categories and did not change interchange fees for the other merchant categories. Two single-message networks, Jeanie and NYCE, decreased both premium and non-premium interchange fees for two or three merchant categories; in the other categories, they decreased one interchange fee and increased the other within a given category. The second group of “both decrease and increase” consists of four single-message networks and one dual-message network, all of which decreased interchange fees for at least one merchant category but increased interchange fees for at least one other merchant category (denoted as “↑” in Table 1). The third “no change” group consists of the two Mastercard networks (Mastercard and Maestro), both of which did not change interchange fees. The fourth “increase” group consists of two single-message networks, which generally increased interchange fees. ACCEL and STAR increased both premium and non-premium interchange fees for grocery stores, general retail merchants, and gas stations; for quick-service restaurants, they decreased non-premium interchange fees but increased premium interchange fees._

Table 1: Changes in Exempt Interchange Fees Charged to Small Merchants by Network and Merchant Category

Notes: “↓” (or “↑”) denotes decrease (or increase) in both the highest and lowest fees or decrease (or increase) in either the highest or lowest fee and no change in the other fee for networks with multiple interchange fees within a given merchant category; or decrease (or increase) in the fee for networks with a single interchange fee within a given merchant category. “↓↑” denotes decrease in either the highest or lowest fees and increase in the other fee within a given merchant category. “→” denotes no change.

Sources: FIS, Hartland, Helcim.com, Mastercard, Monerisusa.com, Pacificisland.publishpath.com, Paymentech, Vantagecard.com, Visa, Wells Fargo, and author’s calculations.

The categories and groupings in Table 1 point to a few initial observations. First, although affiliated networks are separate networks with different interchange fee schedules, they made directionally similar changes in exempt interchange fees. Both Visa and Interlink are in Group 1, both Discover and Pulse are in Group 2, both Mastercard and Maestro are in Group 3, and both ACCEL and STAR are in Group 4. The only affiliated networks that adjusted their fees in different directions are NYCE and Culiance: The former is in Group 1, while the latter is in Group 2.

Second, there are no clear patterns between single-message and dual-message networks or across networks within a given merchant category. The 10 single-message networks are distributed across all four groups and the three dual-message networks are distributed across three groups. For each of the four major merchant categories, some networks decreased exempt interchange fees, some networks increased the fees, and others did not change the fees.

Third, exempt interchange fees in the aggregate do not appear to have fallen for small merchants from 2011 to 2024. Although nine out of 13 networks decreased exempt interchange fees for at least one merchant category, five of these nine networks also increased the fees for at least one merchant category, while the other four networks either increased or did not change the fees. Moreover, the size of the fee increases is generally much greater than that of the fee reductions.

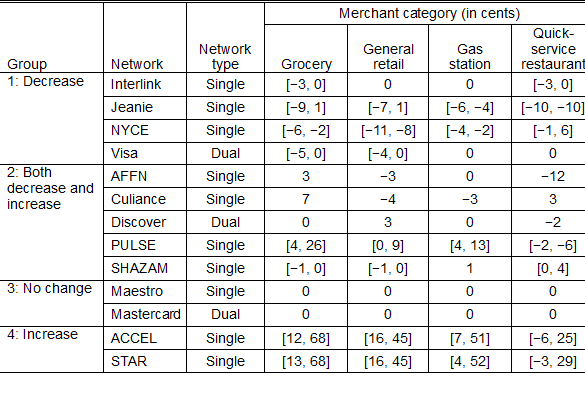

To capture the magnitude of these fee changes, Table 2 presents how much the exempt interchange fees each network changed for each merchant category from October 2011 to August 2024. Changes in Jeanie’s interchange fee for grocery stores, for example, range from a $0.09 reduction to a $0.01 increase. Generally, the size of fee increases (which range from $0.01 to $0.68) is much greater than the size of fee reductions (which range from $0.01 to $0.11). Based on the examined interchange fee schedules, a larger fee increase is typically due to a newly introduced premium fee received by issuers that participate in a preferred issuer program.

Table 2: Range of Exempt Interchange Fee Changes for Small Merchants by Network and Merchant Category

Notes: [ ] shows the range of changes in exempt interchange fees charged to small merchants in cents. The fee changes are calculated for a $40 transaction at grocery stores, general retail merchants, and gas stations, and for a $10 transaction at quick-service restaurants.

Sources: FIS, Hartland, Helcim.com, Mastercard, Monerisusa.com, Pacificisland.publishpath.com, Paymentech, Vantagecard.com, Visa, Wells Fargo, and author’s calculations.

III. Why Didn’t Exempt Interchange Fees Decline for Small Merchants?

Prior to the implementation of Regulation II, networks had an incentive to set higher interchange fees than their rivals. By charging higher fees to merchants and offering the fee revenue to issuers, the networks could attract more issuers and thus raise the transaction volume from the issuers’ debit cards. These higher fees also helped attract issuers into exclusivity contracts with networks and incentivized issuers to impose priority routing to favor a given network.

The second and third provisions of Regulation II have altered the incentives for single-message networks by prohibiting network exclusivity and limitations on routing. Any single-message network seeking to maximize transaction volume may try to avoid charging either the lowest or highest interchange fees in the market._ To comply with the provision that prohibits network exclusivity arrangements, most issuers enable their debit cards to process transactions over one dual-message network, one single-message network affiliated with the dual-message network, and at least one unaffiliated single-message network. If the single-message network sets its interchange fee too high, then more issuers will select it, but merchants will avoid it and route their transactions over the network with the lowest fee among the networks enabled for a given card. On the other hand, if the single-message network sets its interchange fee too low, it will be unable to attract issuers and may lose them to rival networks._

The second and third provisions of Regulation II may also affect the incentives of dual-message networks to some degree. Card issuers typically enable only one dual-message network on their cards, which incentivizes dual-message networks to set higher interchange fees than their rivals. When merchants offer their debit card customers the option of selecting “credit” or “debit” at the point of sale, some issuers encourage their cardholders to choose “credit,” which routes the transaction to the dual-message network. However, not all merchants offer this option and may elect to route the transaction to a single-message network by prompting the customer to enter their PIN. As a result, dual-message networks may have an incentive not to set their exempt interchange fees too high to discourage such merchant behavior._

Although Regulation II gives merchants wider routing options, many small merchants may not be able to take advantage of them. Small merchants often choose a “flat-rate” fee structure offered by merchant acquirers or processors, which involves a single flat rate—for example, 3 percent of the value of a transaction—that includes the interchange fee as well as all other fees charged to merchants (such as network fees and processing fees) for all types of cards and all brands. This simplified fee structure helps small merchants avoid or reduce the resources required to budget for card transactions with very complex interchange fees. However, the flat-rate fee structure does not reflect varying interchange fees across card types and networks, which may remove an incentive for small merchants to take advantage of merchant routing options. In contrast, large merchants typically opt in to an “interchange-plus” fee structure, which assesses each fee individually, and is thus more transparent about all the fees assessed to the merchants, reflecting any fee changes fully and quickly (Hayashi 2013). Merchants that opt in to the interchange-plus fee structure may therefore take advantage of the wider choice of routing.

Because many small merchants may not actively choose the network with the lowest interchange fees to route their transactions, the incentive of debit card networks to set lower interchange fees than rival networks may be particularly weak for small merchants. Some networks may strategically set interchange fees for small merchants that are higher than their rival networks’ fees to entice exempt issuers into a preferred-issuer program, in which issuers commit to a specific level of transaction volume on that network. The same networks, however, may set interchange fees for large merchants that are lower than their rival networks’ fees to entice those merchants to route their higher volume of transactions to that network._

Conclusion

Debit cards are the most used payment method in the United States. During the 2000s, merchants paid increasingly higher interchange fees to accept debit card transactions, and they had limited ability to route transactions to preferred debit card networks. The Durbin Amendment to the Dodd-Frank Act included requirements to address these growing fees and limited routing options, which the Federal Reserve Board implemented with Regulation II in 2011. Although one provision of Regulation II caps debit card interchange fees received by large issuers, interchange fees received by smaller issuers are exempted from the cap and set freely by debit card networks. However, the two other provisions of Regulation II—prohibitions on both network exclusivity and merchant routing restrictions—could increase competition among card networks for merchants, putting downward pressure on exempt interchange fees.

I find that from 2011 to 2024, nine out of 13 networks decreased exempt interchange fees for small merchants in at least one of the four major merchant categories; however, five of these nine networks also increased fees for at least one merchant category, two networks increased their fees across all four categories, and two networks did not change their fees. Moreover, the size of fee increase is generally much greater than that of fee reduction.

Many small merchants may not be able to take advantage of the wider merchant routing options enabled by the two provisions of Regulation II, which may weaken networks’ incentive to set lower interchange fees than their rival networks for small merchants. If a goal of policy is to contain or reduce debit card interchange fees charged to small merchants, other tools may be needed in addition to or in place of ensuring merchant routing options. Many public authorities around the world have taken actions with various tools to contain merchants’ card acceptance costs (Hayashi and others 2024b). The most common tool may be regulatory caps on interchange fees received by all issuers or on the overall merchant fees assessed for a card transaction. The same caps typically apply to both large and small merchants, but some countries focus more on small merchants. For example, lower preferential fee caps have been set for small and medium-sized merchants in South Korea. And although interchange fees have not been regulated in Canada, the Department of Finance has negotiated with credit card networks to voluntarily reduce credit card interchange fees for small merchants since 2014.

Endnotes

-

1

In October 2023, the Federal Reserve Board proposed to reduce the maximum permissible fee to $0.144 plus 0.04 percent of the value of the transaction, plus a fraud-prevention adjustment of $0.013 for eligible issuers.

-

2

Government-administered payment programs and certain reloadable prepaid cards are also exempt from the cap.

-

3

In 2022, the Federal Reserve Board amended Regulation II to specify that the second provision applies to card-not-present transactions such as e-commerce transactions. This amendment reflects the technological progress in the debit card industry. When Regulation II was initially implemented, the market had not yet developed solutions to broadly support single-message networks over which merchants could route card-not-present debit card transactions; however, since then, most networks have introduced capabilities to process such transactions.

-

4

The average value of an exempt transaction for single-message networks declined slightly, from $43 to $39.

-

5

My examination excludes ATH, which has operated in Puerto Rico, due to a lack of data.

-

6

FIS also owned Jeanie through its subsidiary Worldpay, a global merchant acquirer, until FIS and Worldpay became separate companies in 2023.

-

7

Mastercard offered volume discounts in 2024 according to its published fee schedule, and several other networks may also offer these discounts. For example, the U.S. Department of Justice Antitrust Division (2024) alleges that Visa has signed routing contracts with many large merchants granting them a lower fee than listed so long as the volume of the merchants’ transactions routed to the Visa debit network exceeds the committed volume.

-

8

Some networks first decreased and later increased their exempt interchange fees charged to small merchants. For example, ACCEL decreased non-premium interchange fees in 2013 and premium interchange fees in 2017 but increased both fees in 2022. For yearly interchange fees, see Hayashi and others (2024a).

-

9

Single-message networks also have an incentive to set the network fees assessed to merchants lower than their rivals’ fees to attract merchants to route transactions to the network (Hayashi 2013). However, according to the fee schedules made available by merchant acquirers, network fees assessed to small merchants have generally increased after Regulation II.

-

10

See Hayashi (2012) for more detailed discussion.

-

11

More recently, contactless payments (“tap to pay”) using debit cards have become more prevalent. Some of these payments do not offer the option between “credit” or “debit” nor do they prompt the customer to enter a PIN; in these cases, the debit card transactions could be routed to either a dual- or single-message network.

-

12

In its antitrust lawsuit against Visa, the U.S. Department of Justice alleges that Visa’s contracts with some merchants, merchant acquirers, and issuers hinder single-message networks’ ability to compete against Visa (U.S. Department of Justice Antitrust Division 2024).

Publication information: Vol. 110, no. 2

DOI: 10.18651/ER/v110n2Hayashi

References

Federal Reserve Board. 2024. “Regulation II (Debit Card Interchange Fees and Routing) Average Debit Card Interchange Fee by Payment Card Network.” Last updated October 16.

Federal Reserve System. 2011. “The 2010 Federal Reserve Payment Study.” April 5.

Food Marketing Institute. 2011. “Food Marketing Institute Debit Card Swipe Fee Litigation Backgrounder.” November 22.

Hayashi, Fumiko. 2013. “The New Debit Card Regulations: Effects on Merchants, Consumers, and Payments System Efficiency.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Review, vol. 98, no. 1, pp. 89–118.

———. 2012. “The New Debit Card Regulations: Initial Effects on Networks and Banks.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Review, vol. 97, no. 4, pp. 79–115.

Hayashi, Fumiko, Aditi Routh, Sam Baird, and Kennady Schertzer. 2024a. “Credit and Debit Card Interchange Fees Assessed to Merchants in the United States: August 2024 Update.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

———. 2024b. “Public Authority Involvement in Payment Card Markets: Various Countries: August 2024 Update.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

Hayashi, Fumiko, Richard Sullivan, and Stuart Weiner. 2003. A Guide to the ATM and Debit Card Industry. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

U.S. Department of Justice Antitrust Division. 2024. United States v. Visa, Inc., Complaint. Case 1:24-cv-07214. Filed September 24.

The author of this article has no involvement in Regulation II rulemakings by the Federal Reserve Board. This article does not reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Board, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, or any other component of the Federal Reserve System.