In 2023, nearly 730,000 unbanked U.S. households cited the lack of necessary personal identification (ID) required to open a financial account as a reason for being unbanked—an increase from more than 680,000 in 2021 (FDIC 2024). Although this share of unbanked households (13 percent) is small compared with the shares that cited other reasons (such as not enough money to meet minimum balance requirements, privacy concerns, or lack of trust), access to an accepted ID may be a more resolvable concern.

A growing number of cities and counties have begun to offer municipal ID cards, which allow community members to access services within their municipality. In addition, a municipal ID may facilitate access to banking and financial services for unbanked households that lack a federal or state-issued ID. This Payments System Research Briefing provides an overview of municipal ID programs, discusses how municipal IDs may help facilitate access to financial services, and reviews what challenges remain to increasing financial account access through municipal IDs.

Municipal ID programs and benefits

Municipal ID programs provide residents age 14 or older an ID card issued by or with the approval of city or county governments (Center for Popular Democracy 2013). Municipal ID cards feature a photo of the cardholder along with other basic identifying information such as address and date of birth.

The range of documentation accepted to obtain a municipal ID is more extensive than that accepted to obtain a state-issued ID, requiring proof of residency as well as another form of identity (see Tables A-1 and A-2 in the appendix for examples of accepted documents). For example, a U.S. Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN) authorization letter may be accepted as proof of identity and a letter issued by a hospital, health clinic, or social services agency that receives city funding may be accepted to confirm residency for a municipal ID, but neither of these documents would be accepted for a state-issued ID (Center for Popular Democracy 2015). Municipalities differ on the kinds and combinations of documentation they accept as proof of identity and residency based on their population and program design. For example, some municipal ID cards offer prepaid debit functionality, in which case additional documentation may be required.

The benefits associated with municipal ID programs vary depending on the locality, but all municipalities that issue municipal IDs accept them as proof of identity. Some municipal ID programs also provide the cardholder with benefits at local businesses, museums, libraries, and entertainment venues. Some municipal ID programs work with financial institutions to ensure that municipal IDs meet the requirements for ID accepted to open a bank account, and some work with third-party providers to offer optional prepaid debit functionality on the ID card. The financial features of municipal ID programs not only broaden the options available to low-wage workers beyond check-cashing stores and payday lenders, but also provide a safety benefit to those who would otherwise be carrying large amounts of cash to transact.

The first municipal ID program was introduced in 2007 in New Haven, Connecticut; since then, over 40 cities or municipalities in more than a dozen states have undertaken programs for their residents (ImportaMí 2024). Cities offer municipal IDs to assist residents with accessing basic services such as utilities and medical services, as well as to foster a sense of belonging and build trust with law enforcement within communities (Police Executive Research 2021). Municipal IDs may be particularly helpful for vulnerable populations such as youth in foster care; low-income, elderly, or returning residents; people with mental illness and disabilities; people who are unhoused; immigrants; and others who may have difficulty obtaining or retaining other government-issued IDs. Most programs charge a fee of up to $15 for the card; however, discounts may be offered for children, seniors, and low-income residents, and in cases of hardship, fees may be waived altogether.

Municipal ID programs are typically administered by a city’s government or agencies, a private vendor, a community organization, or some combination of these. Government-run municipal ID programs enable close control and oversight, integration with other city services, and coordinated communication about ID use and acceptance by the government offices and agencies that will be interacting with cardholders. Municipal ID programs run by private vendors enable municipalities to avoid some of the initial expense and work of setting up and administering a municipal ID program, as well as manage prepaid debit functionality if it is offered. Municipal ID programs run by community organizations tend to focus on addressing the needs of certain vulnerable communities and advocating for partnerships—for example, with financial institutions to facilitate the acceptance of a municipal ID card to open a bank account.

Municipal IDs and access to bank accounts

Because the documentation required to obtain a municipal ID tends to be broader than that required to obtain a federal or state ID but still aligns with the documentation required to open a bank account, municipal ID programs have the potential to overcome a barrier for some unbanked households. Identification card programs such as those offered by municipalities in California, Illinois, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, New Jersey, and New York have partnered with financial institutions to allow residents to open a bank account with a municipal ID. Approximately 40 banks and credit unions participate across these various programs. Several of the financial institutions that accept municipal IDs are also participants in Bank On, a coalition of local partnerships between government agencies, financial institutions, and community organizations that work together to improve the financial stability of unbanked and underbanked residents in their communities (Bank On n.d.).

New York’s IDNYC municipal card program, which launched in 2015 and now has more than 2 million cardholders, is one example of a municipal ID that allows financial account access. IDNYC has been affirmed by the Federal Reserve, the U.S. Treasury Department, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency as meeting the requirements of federal anti-money laundering laws and regulations for use at banks (Won and Ramos 2024). The IDNYC card has 10 financial institution partners, four of which are Bank On participants, that will accept the card as a form of identification for opening a bank account, thereby creating an opportunity for the city’s 306,000 unbanked households (IDNYC 2024).

Municipal IDs and access to financial services

Some municipal ID programs have worked with third-party providers to offer a prepaid debit card option with their municipal IDs. In the San Francisco Bay Area, Oakland partnered with SF Global, a financial products and services provider, to launch the Oakland City ID in 2009, the first municipal ID to offer a prepaid debit function. In 2011, nearby Richmond followed suit and issued its Richmond City Card. Residents in both cities can reload the card at Western Union, direct-deposit paychecks to it, withdraw cash from it at ATMs, and shop with it anywhere Mastercard is accepted (SF Global 2012). The prepaid debit functionality attached to these programs carry usage fees, including transaction fees, a monthly service charge, ATM withdrawal fees, and various fees for account inquiries. Such fees are known to disincentivize adoption for low-income families. Nevertheless, the debit card function initially proved attractive for the Oakland City ID card. By 2013, Oakland had issued approximately 3,000 IDs, about two-thirds of which were using the debit feature (Wogan 2013).

New Orleans’s Crescent City Card, which soft-launched in 2021, was a quasi-municipal ID card with banking capabilities powered by Mastercard and financial technology company Mobility Capital Finance (MoCaFi). The card was intended to make it easier for city residents to access both banking and city services, included a basic income component, and was piloted with two groups of 125 randomly selected “truly needy” individuals (Liu 2022). The pilot aimed to explore whether a card that had financial services linked to it could also function as a library, school enrollment, and public transportation card. Ultimately, the program managed to provide cards to 76 people, about 60 percent of the original goal, and was deemed to have been a success. After some delay, the Cresent City Card was revived in November 2024 and endorsed by the city’s mayor and council members (Bloom 2024). At the time of this writing, whether prepaid debit will be a function of the relaunched ID is unknown.

Challenges of using municipal IDs to access to financial services

Municipal ID programs have the potential to facilitate access to financial services for households that lack sufficient ID to open a bank account, but this outcome faces challenges. A basic challenge is getting the ID into the hands of the people who need it. Although a greater range of documentation is accepted as proof of identity and residency in applying for a municipal ID, not all documents are given equal weight, and therefore different combinations may be required. For some households, obtaining a municipal ID could be nearly as restrictive as obtaining a state-issued ID.

Another challenge may be getting financial institutions to accept municipal IDs. Of the more than 40 municipal ID programs in effect, only about a quarter allow the cardholder to open a bank account. Financial institution partners are predominantly community banks and credit unions, some of which are also Bank On participants; very few are larger financial institutions. While municipal IDs may resolve the problem of access to identification required to open an account, geographic barriers—being in proximity to participating institutions—may remain. In addition, although federal regulators and some smaller banks have approved the use of municipal IDs for opening a bank account, some financial institution partners only accept it as a secondary form of identification.

Offering access to prepaid debit functionality through municipal IDs also has its challenges. By attaching a prepaid debit function to municipal ID, cities trigger regulations that set a much higher threshold for proof of identity and residency than that set by most cities running municipal ID card programs without a prepaid debit option. Regulations governing prepaid debit cards may also require that vendors retain copies of a cardholder’s underlying application documents for five years, raising concerns over privacy. Another concern is the safekeeping of cardholders’ funds as well as their personal and financial information. Further, the municipality may need to consider the safety and soundness of the third-party’s program as well as the fees associated with the use of prepaid debit cards. Some consumer groups and community organizations have characterized the prepaid debit transaction fees as unacceptably high and have noted that the service falls below the standards of traditional bank services—which essentially places the municipality in the position of perpetuating uneven access to financial services (Badger 2013).

Conclusion

For nearly three-quarters of a million U.S. unbanked households, the lack of an ID necessary to open a bank account is a reason for remaining unbanked. Municipal ID programs may offer a means to address this barrier as well as offer access to other financial services, though they face some challenges to doing so. Synergies between these programs and financial inclusion efforts such as the Bank On coalition may be important for municipal ID programs to make meaningful progress.

Appendix

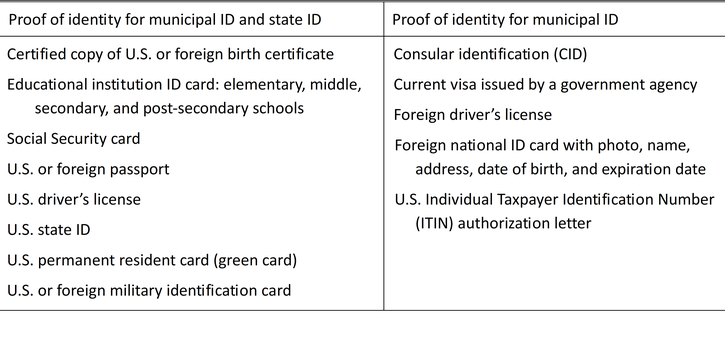

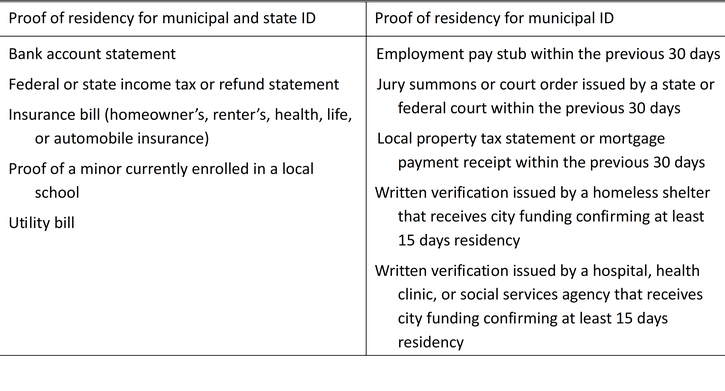

Proof of identity and proof of residency are required to receive a municipal ID card. Table A-1 provides examples of acceptable forms of documentation to prove identity. The left column lists documents that are also acceptable for state-issued ID, but with differing requirements based on the document’s expiration date. Documents that prove identity for municipal ID may be up to 60 days beyond their expiration date versus unexpired for state-issued ID. Table A-2 provides examples of acceptable forms of documentation to prove residency. The left column lists documents that also are acceptable for state-issued ID but may have differing requirements for the length of residency. Residency for municipal ID may be verifiable after 15 days versus 90 days for state-issued ID.

Table A-1: Acceptable Municipal ID Documentation for Proof of Identity

Table A-2: Acceptable Municipal ID Documentation for Proof of Residency

References

Badger, Emily, and National Journal. 2013. “External LinkShould Cities Be in the Business of Issuing Debit Cards?” The Atlantic, August 13.

Bank On. n.d. “External LinkCoalition Map.” Accessed November 20.

Bloom, Matt. 2024. “External LinkNew Orleans Council Approves City ID For Residents.” New Orleans Public Radio, November 8.

Center for Popular Democracy. 2015. External Link“Building Identity: A Toolkit for Designing and Implementing a Successful Municipal ID Program.”

———. 2013. “External LinkWho We Are: Municipal ID Cards as a Local Strategy to Promote Belonging and Shared Community Identity.”

FDIC. 2024. “External Link2023 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households.” November.

IDNYC. 2024. “External LinkBenefits: Banks and Credit Unions.” Nyc.gov, accessed November 15.

ImportaMí. 2024. “External LinkCommunity and Alternative ID Cards.” October 13.

Liu, Michelle. 2022. “External LinkMastercard Gave New Orleans $100K for ‘Truly Needy.’ City Couldn’t Get People to Take Cash.” Louisiana Illuminator, November 8.

Police Executive Research Forum. 2021. “External LinkCommunity-Based Identification Cards Give Immigrants a Sense of Belonging and Trust in Local Police.” June.

SF Global. 2012. “SF Global LLC Letter to Members of the City Council of Los Angeles.” November 2.

Wogan, J.B. 2013. “External LinkOakland’s Debit ID Cards That Aim to Help Unbanked, Immigrants Catching On.” Governing, August 7.

Won, Julie, and Jessica Ramos. 2024. “External LinkOp-ed: It’s Time for New York Banks to Accept IDNYC.” amNY, April 10.

Terri Bradford is an advanced payments specialist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.